Expanding aquaculture at the expense of wild salmon?

Aimed at regulating growth in the Norwegian aquaculture industry, the Government’s new ‘traffic light’ system entered into force on 30 October. But are the standards sufficiently stringent to ensure environmentally sound salmon farming?

According to FNI researcher Ole Kristian Fauchald, the answer is no. In his recently published report, Fauchald investigates the relationship between Norwegian regulations to ensure sustainable growth in the salmon farming industry, on the one hand, and regulations to conserve wild salmon, on the other. The ‘traffic light’ system, he concludes, fails to consider already existing laws that are essential in the allocation and expansion of fish farming licenses – potentially at the expense of the wild salmon.

The ‘traffic light’ system

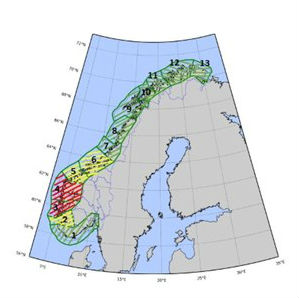

In order to regulate growth in Norway’s aquaculture industry a colour coding scheme – green, yellow and red, hence the ‘traffic light’ system – is used to identify regions where expansion can take place.

As of today, eight of the thirteen production areas have been awarded the colour green. A regulation has been proposed that will allow existing fish farms in these areas to increase their production capacity by 2 per cent. The government is also intending to auction new licences, increasing total production by 6 per cent. The five remaining production areas are coloured yellow or red, and fish farms there are only allowed to expand up to 6 per cent if they fulfil certain predefined criteria.

Taken together, the colours awarded the thirteen production areas define where the aquaculture industry can expand capacity. The colour of each production area is based on a single factor: the prevalence of salmon lice and the damage it causes to wild salmon spawn.

Challenges

However, while reducing the prevalence of salmon lice is important to achieve environmentally sound salmon farming, it is far from alone. In fact, the requirements of the Aquaculture Act and the Nature Diversity Act, including the latter’s quality standards for wild salmon, appear stricter than the ‘traffic light’ system’s. Therefore, some are worried that the status of wild salmon and other environmental challenges associated with salmon farming are not taken sufficiently into account.

What is more, the government has decided in principle that all fish farms in green production areas will be allowed to expand, which might imply that that the protection of potentially endangered populations of wild salmon may not be taken as seriously in these areas.

‘Norwegian authorities have identified 465 distinct salmon populations of  which 148 have been assessed. The results show that the quality standards for 119 of these populations have not been met. In this situation, it would seem irresponsible to initiate a new regulatory regime designed to facilitate expansion in the salmon farming industry insofar as the industry has been identified as the main threat to wild salmon populations’, Fauchald says.

which 148 have been assessed. The results show that the quality standards for 119 of these populations have not been met. In this situation, it would seem irresponsible to initiate a new regulatory regime designed to facilitate expansion in the salmon farming industry insofar as the industry has been identified as the main threat to wild salmon populations’, Fauchald says.

‘My legal assessment of the new regime is that it pays insufficient attention to existing rules adopted to protect the environment. It is therefore not unlikely that the new regime will face a number of stumbling blocks when it is implemented unless the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries implements appropriate procedures before making the final decisions. My report sets out the main elements the Ministry should consider’, Fauchald continues.

Science and policy decisions

The wider process leading to the adoption of the ‘traffic light’ system has suffered from several shortcomings. In spite of being developed by public authorities in close consultation with research institutions, the actual consequences have not been sufficiently identified and assessed.

‘A fundamental principle of Norwegian environmental law has been ecosystem management. This principle was adopted partly in response to progress in the natural sciences regarding the need for more advanced approaches to management of natural resources. However, in this case we see that relevant research institutions have contributed to the establishment of a management regime that is very far from being based on an ecosystem approach. I have been very puzzled by the absence of considerations of the impacts on ecosystems when studying the input from the scientific community to the design of the management regime’, Fauchald explains.

The report was carried out on behalf of Norske Lakseelver, an organization for rights holders to fish in watercourses with salmon, lake trout and sea char. It was delivered to the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries on 15 November.