Fish, not oil, at the heart of the South China Sea conflict

While largely perceived as a fight over oil resources, clashing assertions of sovereignty and competing maritime claims, the heart of the South China Sea conflict is really all about fish.

In fact, the South China Sea may be on the edge of a fisheries collapse, according to Professor Clive Schofield of the Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security (ANCORS) at the University of Wollongong. Schofield, who served as an expert witness in the South China Sea Arbitration between the Philippines and China last year, recently held a mini-seminar at the Fridtjof Nansen Institute, where he gave a tour of the key issues of the conflict and what’s really at stake.

While the South China Sea is a biodiversity-rich tropical sea, supporting abundant fisheries, its unique environment and invaluable marine living resources are in increasing peril. ‘Undoubtedly’, Schofield says, ‘a continued status quo scenario in terms of overfishing in the region is dire’. But how did it get this far?

Clashing claims

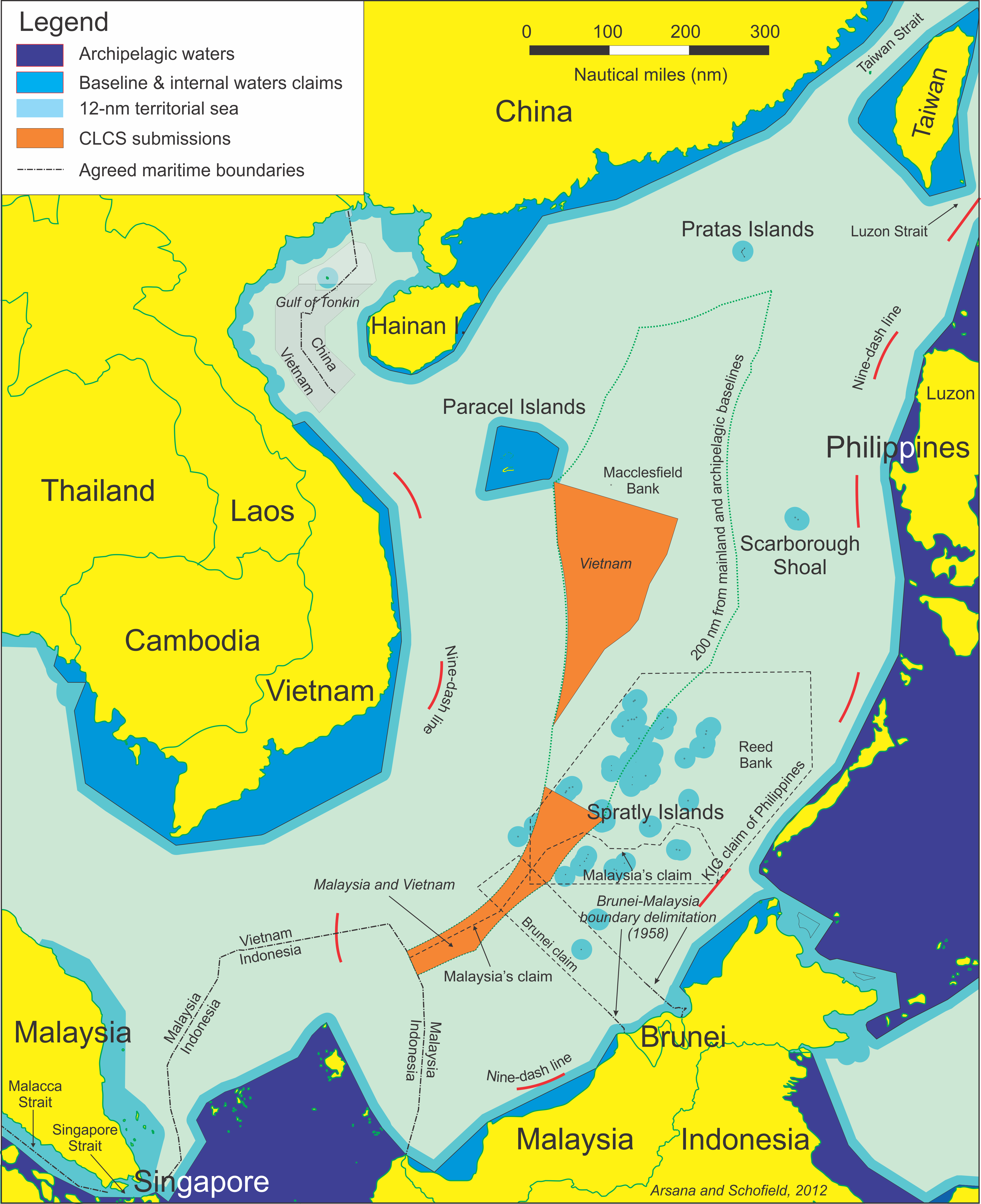

The South China Se a dispute not only involves competing sovereignty claims over a profusion of small islands, rocks, reefs and semi- or fully-submerged maritime features, but broad areas of overlapping maritime claims (see map). Most significant of the disputed groups of islands are the Spratlys, strategically located close to major maritime trading routes carrying products worth an estimated US$3.3 billion (2016). China, Taiwan, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei and Vietnam all claim sovereignty to all or some of the Spratly Islands, and all (except Brunei) occupy and garrison at least one feature.

a dispute not only involves competing sovereignty claims over a profusion of small islands, rocks, reefs and semi- or fully-submerged maritime features, but broad areas of overlapping maritime claims (see map). Most significant of the disputed groups of islands are the Spratlys, strategically located close to major maritime trading routes carrying products worth an estimated US$3.3 billion (2016). China, Taiwan, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei and Vietnam all claim sovereignty to all or some of the Spratly Islands, and all (except Brunei) occupy and garrison at least one feature.

An important underlying dimension feeding into the conflict is access to resources. The seabed around the Spratlys reportedly holds substantial oil and gas reserves – although estimates are speculative and vary greatly. More importantly, the region is host to rich fishing grounds supplying hundreds of millions of people across the region with food and jobs.

The question is who should benefit from these resources. According to Beijing, China is entitled to the lion’s share. Based on historic rights, the country’s so-called Nine-Dash Line covers close to 80 per cent of the South China Sea. However, that claim is contrary to the framework of maritime zones under the UN Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and, of course, rejected by the other South China Sea states.

Free-for-all fishing

After all, the South China Sea fisheries are vital to the economies of the claimant states. The area holds at least 3,365 species of marine fish, 55 per cent of global marine fishing vessels operate in the South China Sea, and some 12 per cent of global fishing catches take place here. Moreover, for fringe states, fish is an extremely important source of nutrition, and fisheries employ at least 3.7 million people.

However, these resources have been overexploited for decades, and are currently under enormous pressure. Fish stocks have declined 70–90 per cent since the 1950s, and overfishing today is exacerbated by the huge scale of illegal unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU).

The ongoing disputes do little to better the situation: The absence of agreed boundaries and a functioning regional fisheries management regime, coupled with decreasing fish stocks and increasing competition, only serves to aggravate the problem.

Towards a solution?

Many were hopeful that the conflict, at least in part, could be softened by the South China Sea Arbitration case, brought by the Philippines against China and heard on 22 January 2013. The ruling, which fell on 12 July 2016, favoured the Philippine stance, thereby demolishing China’s controversial claims.

The arbitration award clarifies some important issues. China’s Nine-Dash Line and historic rights are dismissed, the consequence being that other coastal states can now claim exclusive economic zones (EEZs) of their own under UNCLOS. Further, by determining the legal status of the Spratly Islands as rocks incapable of generating extended maritime zones (EEZ and continental shelf rights), the Tribunal’s ruling could dramatically reduce the extent of waters under dispute, and have an effect on conflicts elsewhere.

‘But there will be strong resistance from key international maritime powers to this ruling. France, the UK, the US and others with strategic island interests, will probably have issues with this ruling,’ says Schofield.

Ruling rejected

Equally important is China’s all out rejection of the jurisdiction of the Tribunal, and thus the validity of its ruling. The Chinese will in all likelihood therefore continue to operate to the limits of the Nine-Dash Line. Given the country’s huge demand for fish, overexploitation is likely to endure. Moreover, China will probably continue to resist the efforts of other coastal states to control waters considered their own. This could lead to further fisheries-related conflicts between rival fishing fleets and maritime enforcement authorities.

With that, few immediate solutions are in sight as fisheries go into collapse.

‘A very dire situation for the millions of people who are directly and indirectly dependent on these fisheries’, says Schofield. ‘Arguably’, he goes on, ‘it may take the sort of food, economic and environmental crisis that such a collapse would entail to generate the political will for change, by which time it may be too late.’